"AND EVERYTHING IN BETWEEN"

☻

"AND EVERYTHING IN BETWEEN" ☻

Writing from Columbus, Ohio

Making Easy, Over Eggs

Originally published on Big Cartel's Workshop.

The hardest part of making my next short film is over.

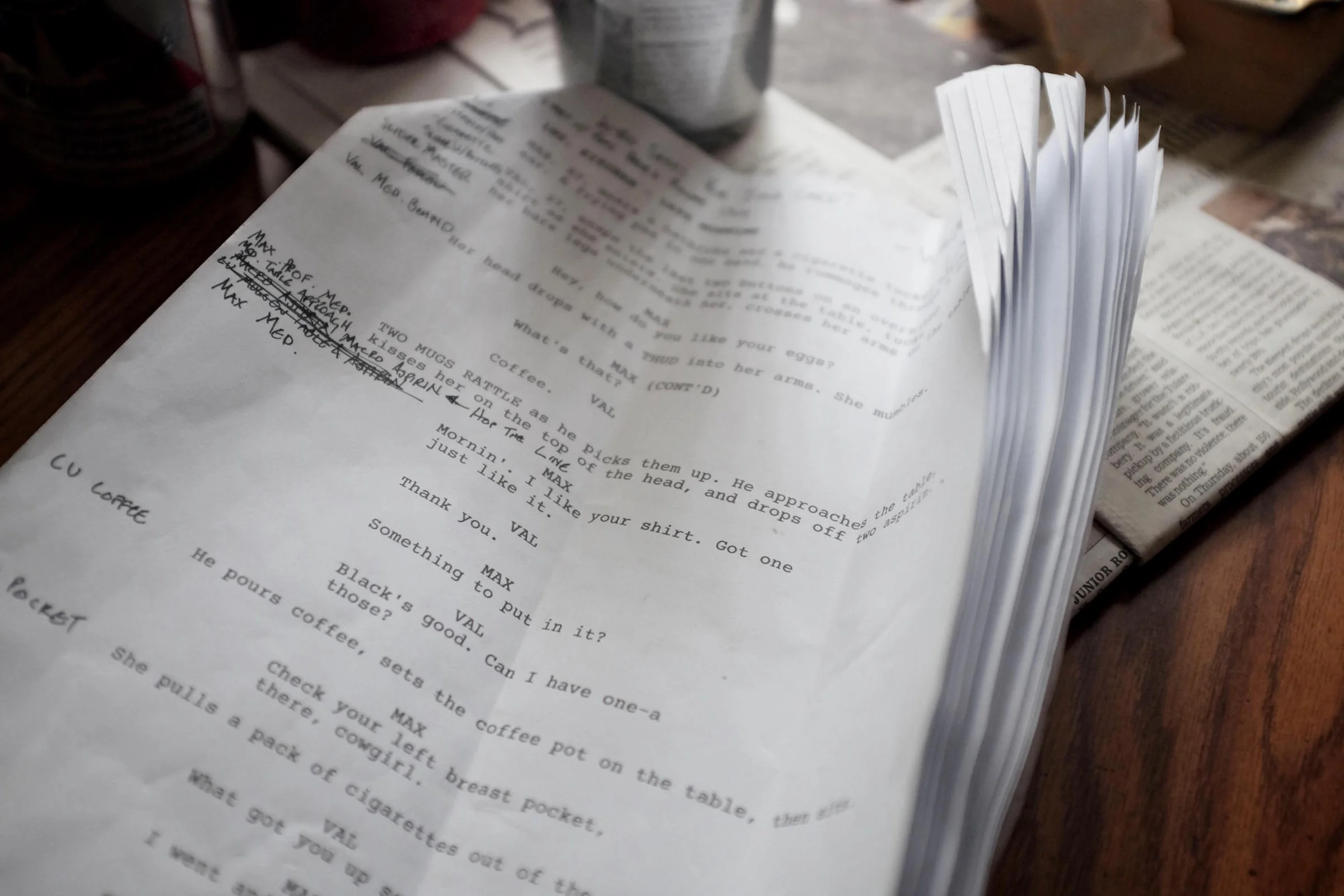

It’s hard to believe it’s been a month now, but on Friday, May 6th, at about 1:55 pm, we wrapped production on my latest short film. Easy, Over Eggs, written by Zach Low and directed by me, is now being edited. In the coming months, we’ll find some music for it. The film will at some point be available to watch. Knowing that now it’s just a matter a time, and not so much a matter of logistics, is a relief.

Pre-production is a stressful part of the filmmaking process that’s not often talked about. Most filmmakers are probably too exhausted when it’s all over to even want to think about it. Leading up to rolling sound and cameras, you have to figure out money, people, locations, and scheduling. You spend months planning for two days of filming to make a 10 minute short film. The amount of time that goes into making a film cannot be understated.

How I prepare to make a film

I watch and read a lot. I hoard ideas and inspiration from others like an animal gathering food as they head into winter. Watching films and reading about how they were made helps me in a couple ways.

First, I learn from their mistakes (and I’m reminded of my own) so I don’t make them. Second, I can find inspiration for things to try. It’s not about watching someone’s work so you can rip it off - it’s so you can make new connections. If I take this piece from here, and that piece from there, and combine them with this original idea, what happens? That’s when you can discover something new and figure out what it is you have to say about it.

This time, though, it was a little different.

About that thing I said

As I wrapped up my last short film in 2014, I wrote:

I don't know that I'll ever make a film that fits a traditional narrative - such as two people sitting at a table talking. And that's OK, because part of what I love about film is that there's so much room to explore.

I thought about that for awhile. I really meant it - I didn’t know if that staple of filmmaking was something I’d ever end up doing. And then, I decided to challenge myself. Why can't I have fun making a movie with two people sitting at a table? Why can't I add the same subtext and nuance to that? And what would it be like to work from someone else's script? I wanted to find out.

Working with someone else's script meant this project wasn't just about my vision, but also the writer's perspective. We collaborated closely, sending about a half dozen versions of the script back and forth over a 3 month period. Most versions only had minor changes, but a couple saw drastic cuts to see how far we could go. In my mind, a big part of filmmaking is to see how much you can say with as little as possible. While the original version of the script was 29 pages and written with the intention of being a stage play, we settled on a shooting script that was around 15 pages, but still felt true to its original vision.

How to make a movie when you’re busy with life

Another big thing that was different time around - I'm making a movie when I have 2 kids. Here's how you do it:

- Work through your lunch break so you can take meetings and make calls.

- Stay up after everyone else is in bed, even though you know you'll have to be up in a couple hours (when your 6-month-old baby wakes up).

- Do it because you have to, because you're compelled to make art.

- Do it because it's fun.

Nothing can stop us now

Well, a few things can stop us.

Less than a month until our production date, and we still hadn’t confirmed a location. Then it’s 2 weeks out and I don't know if we'll be making this thing. This is the time you just want to quit. Pack it up and go home. But you can't. Right?

Most people do quit, though. Making a movie isn’t hard. The individual pieces are hard - finding and scheduling and getting permission and paying for things. Those aren’t easy. Too many people hit the first or second or tenth roadblock and decide that enough's enough. But if you stick with it, it does start to come together.

A week before we were set to film, just as it felt like everything was about to fall apart, the opposite happened - we got things in order, and people offered to pitch in even more than we had asked. Let’s go!

The best analogy I can come up with is this: Making a movie is like wrangling a bunch of marbles on a slick table. Your goal is to get them to all roll in the same direction. The thing is as you push one along, it bumps into another, which sets off a new chain of events. Oh, and the table has holes and spikes and marble-eating monsters. You have to get through with as many marbles - and fingers - left as possible. Things go from completely in control to violently random, until all is calm and everything settles into place.

And then you start filming.

Three ways to begin fixing Silicon Valley's 'pipeline' problem

Originally published on USA TODAY on July 16, 2015.

There's a lot of talk about the "pipeline" as the root cause for technology's lack of diversity—the idea that women and minorities aren't seeking out relevant education, therefore they cannot be hired for technical or executive jobs.

This ignores the fact that the lack of diversity in non-technical roles like administration and sales mirrors a shortfall in technical positions in Silicon Valley. Further evidence shows that current diverse candidates graduating with technical degrees are still not seeing the wealth of opportunities that the technology industry promises.

As Elizabeth Weise and Jessica Guynn of USA TODAY pointed out last fall:

On average, just 2% of technology workers at seven Silicon Valley companies that have released staffing numbers are black; 3% are Hispanic.

But last year, 4.5% of all new recipients of bachelor's degrees in computer science or computer engineering from prestigious research universities were African American, and 6.5% were Hispanic, according to data from the Computing Research Association.

I might work with computers for a living, but I'm pretty sure a pipeline only works when it's used at both ends.

Let's make something clear—when we talk about roadblocks to diversity today, rarely are we pointing to overt bias and discrimination. The issues plaguing Silicon Valley are often subtle practices and biases that snowball into a major imbalance. But I truly believe it's not hard to commit to diversity.

Any expenses to implement better practices will pale in comparison to the long-term financial gain—that is, if simply committing to diversity because it's the right thing to do isn't enough.

If you're a CEO, hiring manager, or decision maker at your company and you'd like to do your part, here are three ways to get serious about diversity.

END EMPLOYEE REFERRAL PROGRAMS

By doing this, you're instantly considering a more diverse pool of applicants.

This is especially important if you offer a bonus to employees for referrals. Take those funds and cover relocation expenses for new hires. If you already reimburse moving costs, now you're saving money!

Current employees who enjoy the bonus might not like this change. The good news is that diverse teams perform better, so you can give those well-performing teams a year-end bonus instead.

You could also find better ways to improve employee life by diverting that money into programs for a quality family leave policy and flexible paid time off.

START A RESIDENCY PROGRAM

Women and minority candidates from schools already tapped into the Silicon Valley pipeline are going without jobs, as the stats above show. This could be for a number of reasons—lacking a network for referrals, inability to afford internships or temporary positions, or unconscious bias. Perhaps the worst example of such bias is that people with stereotypically black names were 50% less likely to be called back for an interview.

Whatever the reason, there's a tested solution to help increase your employee headcount with quality workers: Take a cue from the medical field and start a residency program.

This is a low-risk move that allows companies to hire people that might otherwise be passed over for a perceived (or real) lack of experience. Now you have no excuses.

Train residents for a six to 12-month period while they work on small projects within the company. After completing the residency program, transition these employees to full-time roles.

These programs should be run largely by women and minorities in effort to provide all new residents with multiple examples of traditionally underrepresented people in leadership positions.

If you really care about hiring people from all walks of life, dedicate a large portion of these resident positions to candidates from outside Silicon Valley.

LISTEN TO US

There's no shortage of people doing their best to speak up. Yet, what I see time and time again is a dismissal of these people's experiences or qualifications, including my own.

"You must have been under qualified," or "I'm a white guy and I've experienced that too, so it's not a problem," or "Get over yourself," are common retorts that reinforce the status quo of Silicon Valley's meritocracy myth.

There's a constant effort to silence the voices of people who can see blindspots where others cannot. It's easy to ignore these situations when it doesn't affect you personally, but that doesn't make it the right thing to do.

Addressing Silicon Valley's lack of diversity truly starts by listening to the stories we are trying to tell you. If you ignore us, if you think you know better than us about how to develop an inclusive environment, if you think you can uncover the "real" reason why we aren't getting hired at the rates we deserve:

You are wrong.

Sharing our experiences does not invalidate your own. So just listen.

Listening leads to empathy. Empathy leads to building a better culture.

Doesn't that sound great?

It’s not enough to keep saying Silicon Valley has a diversity problem—we have to get specific

Originally published on Quartz on June 29, 2015.

If we continue saying “Silicon Valley has a diversity problem” without getting specific, how will we ever know what to address?

When I published a post on Medium about my experiences as a black male looking for a job in Silicon Valley, the last thing I expected was for it to get as much attention as it did. It’s not a secret that Silicon Valley has serious issues with diversity—Facebook’s recently-released diversity report proves that hiring practices still have a very long way to go. But the response to my personal perspective on hiring discrimination is a reminder of just how much that issue continues to resonated with people from all walks of life. Indeed, many of the issues and anxieties that underrepresented people encounter are universal, as is the desire to address them.

Maybe it’s a parent expected to go out for drinks after work despite family obligations, or an LGBTQ person weighing an offer that provides unequal pay or benefits, or a person who realizes that their dream job is an impossibility given the prohibitive cost of moving to San Francisco. These are the people on the margins—forced out, or not let in at all. Diversity is important, but especially so in the corporate and tech world. It’s not a coincidence that diverse teams perform better.

When I criticize industry practices, I do so in the hopes that I will help further the conversation on technology’s diversity problem. To do this, we must continue to talk about the systems and mindsets that lead to such a homogeneous culture. Practices like relying on referrals for new hires, or offering unpaid internships and temporary contract positions might seem beneficial to a company’s bottom line, but in actuality they dramatically reduce and limit the pool of candidates for any job opening.

The good news is there are discernible strategies that could help. We can start by supporting underrepresented people, whether that’s monetarily or simply by considering whose voices we amplify on social media. When scheduling a conference, include speakers of all backgrounds, even if that means looking for experts outside of your network. If you don’t believe that’s possible, just look at conferences like AlterConf, Tech Inclusion, and XOXO.

Honesty and transparency are essential. I still see many influential tech companies refusing to publicly acknowledging there’s a diversity gap at all. Reading something as simple as, “We know diversity in technology isn’t where it needs to be, and we want to fix that,” on a job posting goes a long way for candidates who notice the job’s employee page doesn’t feature any people who look like them.

We also need to examine hiring practices and benefits for evidence of hidden biases. If you’re willing to hire someone and pay a tech-industry salary, I have to believe that offering a small relocation credit is worth your long-term investment. (To me, that seems much more valuable than an in-office ping-pong table or fully stocked fridge.)

Finally, support your current employees. I’m able to speak up because I know my employer, Big Cartel, stands with me. I don’t have to worry that speaking out will negatively impact my employment status. But that’s not always the case. How many voices are quieted because they don’t have that privilege?

Right now, there are people in your company who care about this. Deeply. Ask yourself if there are ways to give them a platform. Extend an invitation to involve them in discussions about diversity if they’re interested. (If they’re not, respect that decision, too!) This is about opportunity equality for all. This is about building companies that better represent the diverse world we live in. The only way meaningful change will take place is if those underrepresented people are empowered to contribute to the conversation. That starts by those in positions of power — CEO’s, hiring managers, conference organizers — making diversity a priority, and not another checkbox.

The Amazon thing

On Saturday, The New York Times published a piece by Jodi Kantor and David Streitfeld titled, “Inside Amazon: Wrestling Big Ideas in a Bruising Workplace.” Maybe the most critical line of the whole story comes near the end:

Noelle Barnes, who worked in marketing for Amazon for nine years, repeated a saying around campus: “Amazon is where overachievers go to feel bad about themselves.”

To say there’s been a big reaction to the article would be an understatement.

One of the primary criticisms seems to be that the piece isn’t balanced and that it’s overly negative. I don’t wholly disagree with that reaction. It does feel like the reporters had their conclusion very early on and used their reporting to write the piece they wanted. Is it wrong to take that decision away from the reader?

Whatever your stance, it shouldn’t be very surprising that a company whose mission is to figure out how to deliver orders in under an hour would have harsh working conditions. Let’s hear more stories from the warehouse workers.

But here’s the thing: it doesn’t matter if the piece was overly negative, or even a little unfair. A number of people were interviewed by the Times, and I simply won’t discount their experiences or their truth. This story matters not just in the context of Amazon, but also in the context of addressing technology’s diversity issues.

With that in mind, David of 37Signals has the best take I’ve read on this situation, the report, and Amazon’s response:

How you respond to a red flag is what matters. You can deny its very existence. You can argue that it’s not really red, but more of an orange pink. You can argue that the people holding the flag aren’t true Amazonians. You can argue that the people who caused the red flags to fly were rogue actors, going against the intentions of the company. Or you can simply just claim that since you hadn’t personally seen any of the incidents, the flags are illegitimate on their face.

But the bottom line is that culture is what culture does. Culture isn’t what you intend it to be. It’s not what you hope or aspire for it to be. It’s what you do. There’s no way to discredit, deflect, or diffuse that basic truth.

We wonder why technology isn’t diverse, and yet when people speak up, even anonymously, the first reaction of many is to discredit the source.

I don’t care if each experience reported in the Times story was an isolated incident. It’s still important. These pieces add up. They build a narrative of unfair treatment and bias. The initial reaction shouldn’t be to say these stories aren’t true, or that they’re unfair. The initial reaction should be to press Amazon, a 20-year-old company and one of the most successful in the world, to do better.

On diversity in technology

I've had the chance to write about diversity in technology over the past month. It was sparked by a 750ish word post on Medium titled, "A black man walks into Silicon Valley and tries to get a job..."

It was a personal, honestly slightly embarrassing, accounting of what I experienced trying to get a job in technology for four years. But I didn't write that post for me. I wrote that because, now that I have a job I love with a company I adore, I know there are still people out there struggling to overcome those same hurdles every day. That's why it resonated and spread far throughout the internet. If my writing can help just one person - especially if it can open one more hiring manager's eyes or CEO's minds to unconscious bias and privilege - then it was worth it.

That post was later republished on Fusion, thanks to Kevin Roose wanting to amplify my story.

After that, Meredith Bennett-Smith of Quartz asked if I was interested in republishing that piece or writing more, and I took that chance to get more specific. In my mind, he only way to properly critique and address the issues of diversity in Silicon Valley is by being direct. Pointing out specific issues and suggesting real solutions is better than beating around the bush or choruses of "we have work to do."

Shortly after my post on Medium gained a lot of attention, USA TODAY technology reporter Jessica Guynn connected with me and offered support. She's long reported on the topics and statistics that others are only beginning to see. She extended an offer for USA TODAY to possibly run some of my writing, which led to me publishing "Three ways to begin fixing Silicon Valley's 'pipeline' problem."

I'm continuing to think about how I can best help those who aren't getting a chance. People who love art and technology but aren't being represented in the work they see. And it's great to know Big Cartel is behind me.

Below is the original post that started it all.

- - - - -

For a long time, I dreamt to work in Silicon Valley. That dream is dead.

I’d like to tell you a joke. But first, some backstory.

I applied for hundreds of jobs (not an exaggeration) after college, many in the Bay Area. I had a few interviews — I was even flown out twice by one company — but I remained without my first “adult” job for over four years.

Hiring managers didn’t like me because I went to a small private university in Ohio. They said I didn’t have enough experience — despite graduating with Honors from said college, being a member of the National Communication Honor Society, and holding a part-time job and internship for three of my four years in school.

Or, get this — I was also told my experience made me overqualified for the position and they were afraid I’d get bored.

The formula was largely the same. Most I didn’t hear back from at all. With a few, I had an in-person or Skype interview with the team.

Once I got on Skype, one position at a hot tech company changed from full-time to a three-month contract. It was listed on their site as full-time. Oh, and they wouldn’t reimburse any moving costs. One more interesting tidbit: This rejection took place in 2011. Until I found a job last year, I still couldn’t reapply for any new positions. Their hiring system blocked new applications.

Another position suddenly “needed filled immediately,” so they went with someone local. I was told a future position might be available if I planned to relocate. Which I would have if, you know, I had been offered a job. They also wouldn’t reimburse moving costs.

Most of the rest ended the same: silence. Many times I couldn’t even get a courtesy rejection email.

I don’t know that any of this had to do with my race, but twice is a coincidence, three times is a pattern. (A fitting misquote I recently heard of an Ian Fleming quote.) At best (or worst?), it revealed the number of ways Silicon Valley takes care of those close to home, and keeps those on the outside away.

The culture Silicon Valley has built doesn’t value what I bring to the table — my experience, perspective, and talent. To them I simply don’t fill enough checkboxes. I’m not a culture fit, a friend of a friend, or a Stanford grad that could afford to live in San Francisco while job hunting.

The culture doesn’t value evenings and weekends as a time for family, personal development and health, or hobbies. Late nights are meant for hackathons and beer bashes.

This is how you develop a culture that isn’t diverse. You make it impossible for people who can’t afford to take a tryout across the country.That leaves most job openings only available to people whose parents pay their bills; for people who didn’t have to finance their way through college; for people who don’t have, or intend to have, a significant other or children in the near future.

The good news: my dream to work in Silicon Valley is dead because I’ve found out what it’s like to work for a company that values me.

I found a company that values me that’s based in Salt Lake City. Yeah, a company in Utah is doing more for diversity than many in Silicon Valley — get over your biases of where you believe real change is championed.

One of the ways my company encourages diversity is by providing fair pay and benefits for all; which includes reimbursement for relocation, the opportunity to work remotely, a generous family leave policy, and flexible scheduling for personal needs. We also own up to a lack of diversity in job postings, rather than hide the problem. We’re supporting projects and events that emphasize inclusion in tech. Also, hiring doesn’t rely solely on existing social networks.

To Silicon Valley: What legacy are you leaving for your children? If you really believe design can change the world — what legacy are you leaving for the history books? Do you want to be looked back on as a white boy’s club? As an embarrassing furthering of unfair privilege by the most valuable companies of our time?

Or do you really want to change the world?

So, to finish my joke from before: A black man walks into Silicon Valley and tries to get a job, and he leaves empty handed.

Nick Fancher's Studio Anywhere

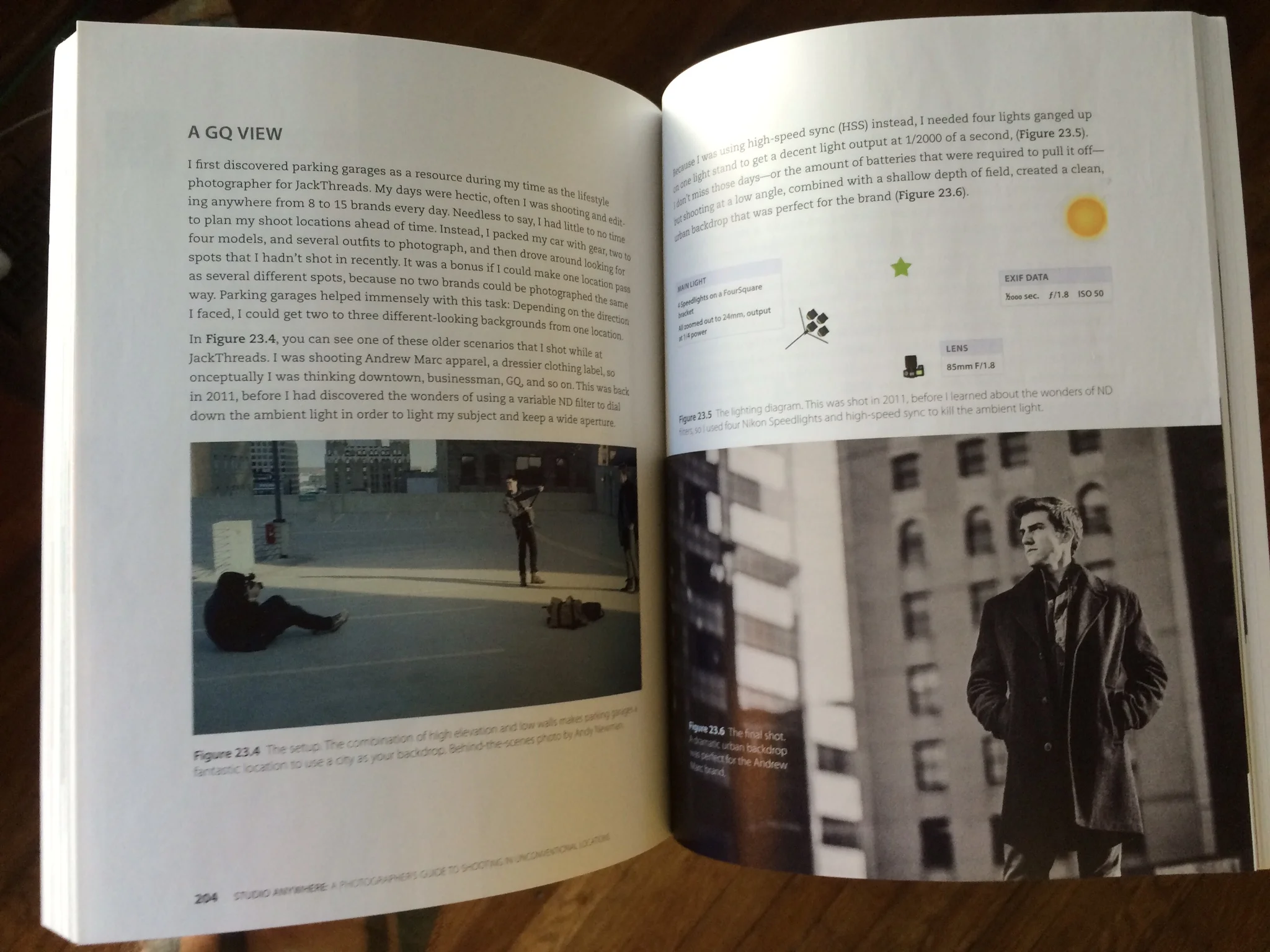

When I first met Nick Fancher, he was working at JackThreads doing almost all of their photography. I was brought in to do some small video projects, so our work overlapped here and there. JackThreads as a company and Nick personally gave me my first shot at doing real independent and creative projects back in 2011 - it was equal parts good luck, hard work, and the right timing.

Towards the end of the year, Nick asked if I would shoot a little behind the scenes video of his photo work. I said yes, of course, but had no idea what it would lead to.

I filmed Nick for about six hours, and spent a few solid days editing a short behind the scenes documentary that became Street Fashion Photography. He entered it into FStoppers' Behind the Scenes contest and we made it to the final 11. Although we didn't win, the video was featured all over popular photography blogs, and today sits at nearly 130,000 views. I still get comments from people telling me how much they like that video almost four years later.

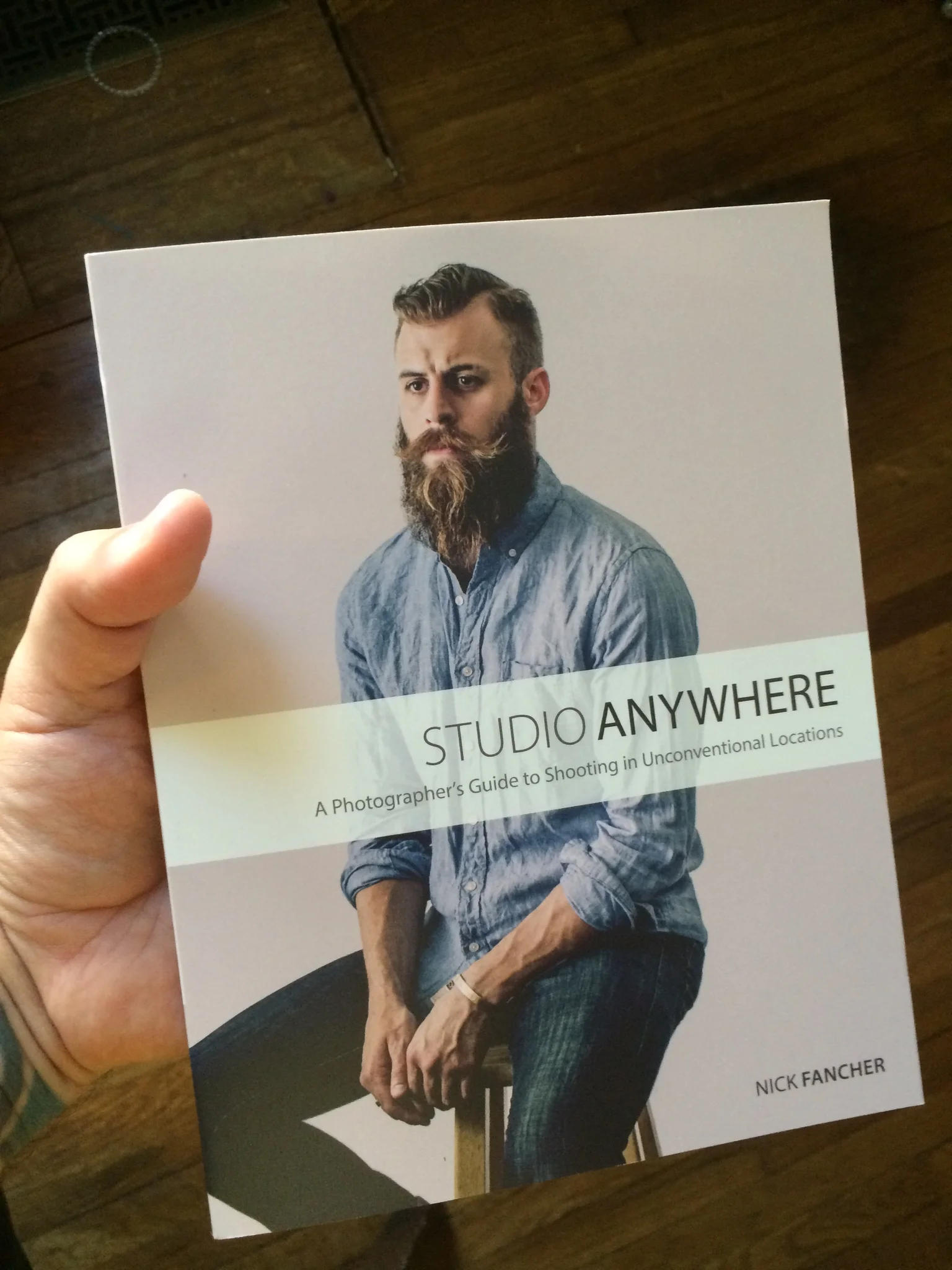

Long before I met him, but especially in the four years since, Nick has been working hard to perfect his craft. Earlier this year he released a book based on his approach, methods, and philosophy called Studio Anywhere: A Photographer's Guide to Shooting in Unconventional Locations.

Here's a brief description of the book from Peachpit's website:

Studio Anywhere is a resource for photographers to learn through behind-the-scenes photos and lighting diagrams from a range of photo shoots–but it doesn’t stop there. Because directing a photo shoot involves more than simply knowing how to wield a camera or process a raw file, Nick also lets you in on the aesthetic decisions he makes in his signature photos, inspiring you to develop your own vision. And, finally, he describes his Lightroom and Photoshop workflow so you can learn how to deftly navigate post-processing.

Nick included a shot from our behind the scenes video in his book, which is so rad! A still of my video work in a book!

A little over a year ago, I caught up with Nick again for my short documentary series Why We Create. He talks more about his process and what drives him to do his best work. Watch it and then go buy his book.

Why representation in film matters

Because everyone deserves to see stories, characters, and situations they can identify with. Laura writes:

Watching Fury Road, I felt like I was watching my own struggle brought to life (albeit in a very fantastical setting), and I don’t think I ever realized how truly profound that could be for me.

Why I share all my secrets

Billionaire investor Chris Sacca, whose investments include Twitter, Kickstarter, and Instagram among others, was recently on Tim Ferriss' podcast, The Tim Ferriss Show.

He brought up a good point about why he openly shares his investing strategies and secrets. It really underscored why I share as much as I have about freelance work and filmmaking here on my blog, culminating in my 11,000-word essay on Medium, The Little Freelance Handbook.

You can listen to the podcast here, but to paraphrase Chris' reasoning:

Sharing secrets or strategies only takes you so far. It requires execution to actually have success with those tips. If you don't have the passion, or frankly, the skill to compete, then it doesn't matter how much I share. But if you do, and the advice given helps you even just a little bit, you'll be an ally for life.

Watch this short film: No Return

New short film written and directed by my good friend Zach Frankart. I helped with cinematography on this film, shooting with Canon 5D Mark III's along with Zach and Johnny Hochstetler. Be sure to watch it and leave a rating on IMDb. (No Return contains violence and strong language.)

Here’s how to make someone buy your $3,500 product

Inspire your customers with benefits, not features

Weeks later, people are still talking about the Apple Watch. Despite the fact that very few people I know actually ordered one. Of those that did order, many haven’t yet received their watch.

Meanwhile, Tesla recently announced the Powerwall, which has gone on to generate a healthy reservation list, but has done little by way of generating actual conversation.

Why is that?

It’s all about framing the conversation. Apple talks benefits, not features. We see a picture of a stupid Chipotle burrito button and can’t share it fast enough. It’s silly, but we can start to piece together the little ways a device like the Apple Watch can reduce friction in our lives — whether at the airport, the checkout counter, or when tracking our fitness levels. But so few companies inspire thinking in that way.

Apple does it. So does Nike. There’s at least one company that should be included in that discussion, but isn’t yet: Tesla

And it’s their own fault.

What if Tesla simply said, “What would you do with an extra $100,000?”

With the introduction of Tesla Energy and its sleek product Powerwall, an opportunity was missed to truly inspire consumers. 38,000 reservations is a number to be proud of, but it should’ve been ten times that.

Here’s how sections of the product page read. Notice how it slips between touching on benefits and falling back on its features. That’s fine when you have a product to put in people’s hands. When you’re trying to generate buzz and sell something completely new, it’s harder to picture in your mind.

Powerwall is a home battery that charges using electricity generated from solar panels, or when utility rates are low, and powers your home in the evening. It also fortifies your home against power outages by providing a backup electricity supply. Automated, compact and simple to install, Powerwall offers independence from the utility grid and the security of an emergency backup.

Not bad, although it’s not really inspiring me to run and find my credit card. Sounds like a fancy backup power supply — I haven’t needed one, so I definitely don’t need an expensive one.

The average home uses more electricity in the morning and evening than during the day when solar energy is plentiful. Without a home battery, excess solar energy is often sold to the power company and purchased back in the evening. This mismatch adds demand on power plants and increases carbon emissions. Powerwall bridges this gap between renewable energy supply and demand by making your home’s solar energy available to you when you need it.

I’ll take your word for it.

Current generation home batteries are bulky, expensive to install and expensive to maintain. In contrast, Powerwall’s lithium ion battery inherits Tesla’s proven automotive battery technology to power your home safely and economically. Completely automated, it installs easily and requires no maintenance.

Yeah.

Powerwall comes in 10 kWh weekly cycle and 7 kWh daily cycle models. Both are guaranteed for ten years and are sufficient to power most homes during peak evening hours. Multiple batteries may be installed together for homes with greater energy need, up to 90 kWh total for the 10 kWh battery and 63 kWh total for the 7 kWh battery.

Oh. I’m not sure how many kWh I use though. Am I supposed to math?

Look, I’m not trying to blast what I’m sure are incredibly genuine people who are trying to communicate very complex and important ideas to the masses. It’s easier said than done. I applaud Elon Musk and the entire Tesla team for what they’re doing — and I wouldn’t compare them to Apple or Nike if I didn’t believe they were capable of amazing feats.

Here’s all Tesla needed to do to sell the Powerwall

Right now, you pay an average of $2,200 per year on energy. Not to mention the stress our current forms of energy are placing on the environment and our one and only earth. A lifetime’s worth of energy comes bundled with staggering hidden costs.

What if you could change that with a single product?

Tesla’s Powerwall is here to help you do just that. For less than the cost of two years of energy bills, you can use a green, renewable energy source that will save you more than $100,000 over your lifetime. Most importantly, it will leave a positive imprint for all generations to follow.

The future of energy is here. We want to save you $100,000, making more money available to invest in you, your family, and the livelihood of all.

Will you join us?

Recommended reading: Other Halves

From Frank Chimero's Other Halves:

Knowledge work has its name for a reason: the challenges naturally swing towards the cerebral, and doubly so if you work in design for digital products. You spend hours and hours considering ways to think about what is ultimately an immaterial thing. And who’s to know if it’s done or right?

Writing is a lot like that, too. So, on average, most of my waking hours are spent wrestling with ghosts.

Understanding Art: A case study of The Death of Socrates

After watching this video essay by Evan Puschak, you'll likely never look at paintings the same way again.

The Creative Process

This is adapted from a Backer's Only update for my Kickstarter project Portrait, originally posted on June 4, 2012.

- - -

I've been doing a lot of preparation and planning for my trip to Seattle - where my production partner Zach and I will be heading to film Portrait!

As much as this film will be about photography, the biggest focus will be on the creative process. What does it mean to be a creative and to chase your dreams? More importantly, how do you construct those dreams in reality and translate an internal inspiration into something others can enjoy? A lot of it comes down to design. Just as Apple designs an amazing product, a filmmaker designs a great film, or a photographer designs the picture hanging on your wall. It's years of practice, learning, and inspiration that make up various parts of the design process.

I've been reading Frank Chimero's The Shape of Design to look at the different ways to approach the topic of design and creative process. From the book:

"First, design is imagining a future and working toward it with intelligence and cleverness. We use design to close the gap between the situation we have and the one we desire. Second, design is a practice built upon making things for other people. We are all on the road together."

I highly recommend buying his book. You can get the digital version for $10 or a hardcover for $30 here.

I've also revisited Walter Isaacson's Steve Jobs. Steve believed in design and being a true artist with your work. When he was younger, he talked about getting older and looking to the future:

"Your thoughts construct patterns like scaffolding in your mind. You are really etching chemical patterns. In most cases, people get stuck in those patterns, just like grooves in a record, and they never get out of them."

He goes on to say:

"If you want to live your life in a creative way, as an artist, you have to not look back too much. You have to be willing to take whatever you've done and whoever you were and throw them away.

The more the outside world tries to reinforce an image of you, the harder it is to continue to be an artist, which is why a lot of times, artists have to say, "Bye. I have to go. I'm going crazy and I'm getting out of here." And they go and hibernate somewhere. Maybe later they re-emerge a little differently."

I feel like both of these are fitting definitions for the creative process.

- - -

You can watch Portrait here.

Art

Art is not - and should never be - all things to all people. Every picture has a unique lens through which the photographer presses her shutter-release button. Every novel has a different set of experiences the writer brings as he sits down in front of his computer or with pencil and paper.

There will always be margins. Gaps in coverage. Pieces of the conversation left out intentionally or unintentionally.

Art should consider all people, because art is about people and our expression. But it doesn't need to represent, or speak for, or even speak to, all people.

Art is honest. Art is raw. It makes you feel, makes you think, makes you cry, makes you angry. But some art may not affect you personally. And that's ok.

The Web's Grain

Frank Chimero on designing without borders:

Edgelessness is in the web’s structure: it’s comprised of individual pages linked together, so its structure can branch out forever.

Edgelessness applies to the screens that show the web, because they offer an infinite canvas that can scroll in any direction for however long. Boy, do we take for granted that a screen can show more content than is able to be displayed in a single shot.

Later, he continues:

A quick example from my life: Twitter didn’t replace Facebook. The iPad didn’t replace my phone. My phone didn’t replace my TV. Now, I watch YouTube on my iPad, toss the video up to my TV, while checking Twitter and Facebook on my phone. It’s a little constellation of technology. But I keep asking myself: how many more things can I juggle? And for how long?

Read the whole thing - it's a storytelling and design experience that shouldn't be missed by anyone with any interest in how designing for the internet should work.

If you look hard enough, it translates to all forms of storytelling. One film-related example is crafting an interactive documentary experience, like Elaine McMillon's Hollow. Or any modern marketing campaign. It's about taking little pieces of a larger whole - a picture here, a tweet there, and creating a cohesive message that connects you with people who want to see your work. It's like a sophisticated method of tearing a bunch of pages out of a book and piecing them back together side by side.

Designing the perfect stapler

Ian Parker profiles Apple's Jony Ive for The New Yorker:

According to Clive Grinyer, “Jon’s always wanted to do luxury.” By this point, Grinyer said, Ive had already fulfilled one duty of industrial design: to design a perfect stapler, for everyone, in a world of lousy staplers. (Most designers driven by that philosophy “didn’t really rule the world,” Grinyer said. “They just ruled staplers.”)

The key to designing the perfect stapler, in my mind, is to make paper nearly obsolete by designing the iPhone, iPad, and Mac.

The retroactive reaction

When will we stop missing the bigger issue?

The following is from Jon Ronson, writing an adaptation from his upcoming book, “So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed,” for The New York Times Magazine. On Justine Sacco:

Sacco had been three hours or so into her flight when retweets of her joke began to overwhelm my Twitter feed. I could understand why some people found it offensive. Read literally, she said that white people don’t get AIDS, but it seems doubtful many interpreted it that way. More likely it was her apparently gleeful flaunting of her privilege that angered people. But after thinking about her tweet for a few seconds more, I began to suspect that it wasn’t racist but a reflexive critique of white privilege — on our tendency to naïvely imagine ourselves immune from life’s horrors. Sacco, like Stone, had been yanked violently out of the context of her small social circle. Right?

Sam Biddle for Gawker in a mea culpa of sorts:

Justine Sacco has a PR job she enjoys now, but she deserves the best and biggest PR job, whatever that may be. Give it all to her.

These articles, while important for entirely different reasons, are missing the bigger issue. They’re looking at a woman against a mob, which is certainly one angle, but I believe a more pressing conversation could have come from this situation. This was a chance to begin a conversation about the mentality of white free-from-consequence privilge. Instead, we seem to be set to perpetuate that privilge.

A day after this happened, back on December 21, 2013, I wrote about this. Some of it will be quoted below. I still stand behind every word I wrote.

Perpetuating her privilge is why comments coming from white guys like Ronson, Biddle, and Dave Pell claiming, “It was almost all about fun and entertainment,” really piss me off. I’m not going to rail on any of these writers for having blind spots, but I do have a problem with them putting everyone in buckets, and more or less apologizing for her after the fact. What she said was terrible. Yet, the overreaction following has absolutely nothing—nothing—to do with the real issue here: Why it was wrong for a person whose job title included the words senior public relations to ever say that in a public forum.

They may claim, “Of course it was awful! I would never condone anything like that,” and I would believe them. I don’t doubt that they’re good people. That still doesn’t change this attempt (by a PR professional, no less) to whitewash this incident after the fact. To make the top Google search result a positive Justine Sacco story, instead of a critical conversation about race.

Job well done.

So, as for my question from 14 months ago:

Although she now finds herself without a job, that simply sweeps the issue under the rug. The internet feels like they won. And while someone who probably should not have been in a high ranking position at a huge company like IAC (About.com, Dictionary.com, Match.com, CollegeHumor, Vimeo, and many more websites you’ve heard of) lost her job, did she — or anyone, for that matter — actually learn anything?

The answer is a resounding, “No.”

Now, there is absolutely a point to be made by those quoted before. The mob mentality of the internet is downright dangerous. One thing I made sure to be very clear about in my original post was the following:

[She doesn’t deserve] to be torn apart for the downright dumb things [she] said this week. Nothing should condone violence. Anyone threatening Ms. Sacco for her racist remark is just as wrong as she was when she hit “Tweet.”

But I’d argue there’s better causes right under their noses worth calling out than trying to clear the name of Justine Sacco.

No matter how innocent her intent, no matter her family history, no matter the inappropriate response of many (most?), some things have not changed.

Like this:

I have to interview with people like Ms. Sacco if I want a job in communication or marketing … And while it’d be just as wrong of me to generalize every white person in a managerial position at every company, hearing comments like this are harder and harder to digest when I get rejection letter after rejection letter.

This still hasn’t changed:

How am I supposed to feel when I see company websites featuring pictures of their employees and not a single one is black?

Or this:

It’s not about ignoring color, or gender, or sexuality. I know many gay people who are all extremely proud of their sexuality, as they should be, and pretending like their sexuality doesn’t exist is just as unfair.

But most of all:

It’s about understanding that when you surround yourself only with people who look, and talk, and act like you — you can’t pretend to know how someone else feels.

And finally:

Ms. Sacco can delete her Twitter account (and she has) and while she’s currently without a job, I doubt it will be a permanent situation. If over 1.7 million people support Phil Robertson, I’m sure she’ll find at least one who supports her.

But the rest of us can’t change our skin color, or gender, or sexual orientation. And that’s why comments like this are not ok.

We wonder why diversity in tech is almost nonexistent, but then we’re willing to so quickly move on from this. We’re willing to ignore the attitude that shapes the culture that influences the hiring decisions.

She wasn’t doing her best Stephen Colbert impression. She wasn’t writing headlines for The Onion. Instead, she posted a bad joke on her personal Twitter account to only a handful of friends and followers, mixed in between what were completely average, benign tweets.

Am I the only one that finds it dangerous to retroactively file that under “satire”?

Interview with DP Bradford Young

Bradford Young, director of photography for films including Selma, Ain't Them Bodies Saints, and A Most Violent Year in an interview with Grantland:

Filmmaking isn’t considered an art form in America, it’s considered a business first and foremost. Those who are artists, who get a chance to say something in the context of a business outfit, are the lucky ones, and they are far and few between. There are not a lot of us who can say we’re artists working in the film context. Basically, all this reminds us is that we’ve got to know who we are, we’ve got to remember who we are, and we’ve got to know that we come from culture and we come from stories, and stories are not about fact. Storytelling is the oldest art form in the world, and what it consists of is allegory and mythology. Stories were never sanctioned to be real, that’s not why we do what we do.

Paul Thomas Anderson's Filmography

From Still Smokin': An Interview with Paul Thomas Anderson by David Ehrlich:

Save for perhaps Punch-Drunk Love, which exists in the sweet synesthesia of its own dimension, each of Anderson’s films is a time capsule, a period piece, or both. With each successive feature, it grows ever more tempting to re-arrange his features by the chronology of their stories and look at his body of work as an alternate history of 20th century America. Anderson may not see much value in such an exercise (“Fuck. I mean, that would be cool, I guess. That would be wild!”), but his films nevertheless evince an uncanny ability to recreate the past so that it feels ineffably present.

I'm going to do that one day.